by Diana Stephens

It has been over 200 years since we’ve seen a Trumpeter Swan here in the Granite State, until last spring, when the excitement at the Audubon headquarters was palpable. The buzz around the office was that there was a Trumpeter Swan being seen at the Abe Emerson Marsh in Candia. Word of the bird’s presence was spreading and the NH Birds Google group was blowing up. The reason for this elation was that the last recorded sighting of a Trumpeter Swan in New Hampshire was in 1784.

From New Hampshire Bird Records

This article is published in the Spring 2019 issue of New Hampshire Bird Records (Vol. 38, No. 1), NH Audubon’s publication all about birds and birding.

The sighting of a single Cygnus buccinator was first reported on April 13, 2019 by Kevin Murphy on eBird, but the bird was initially identified as a Tundra Swan, a species that looks almost identical to the Trumpeter. It was relocated the next day by Leo McKillop, who photographed the bird and then correctly identified it as a Trumpeter. This large, elegant waterbird has been spotted on and off in the marsh since then and has been photographed by many interested observers. A number of passionate birders have pulled off the highway, risking their safety to catch a glimpse of this rare swan in the wetland below. Others have bushwhacked their way into the edge of the marsh with their binoculars for a better view and still others were castigated for getting too close and disturbing the bird. This swan has been observed swimming, eating plants below the surface of the water, sitting on a small mound in the marsh and flying from one pond to another. As of this writing, the gender of the swan is unknown. The bird is not banded, so we cannot know for sure from whence it came or where it will go. Many birders have wondered about this lone swan, paddling by itself in the marsh. Hopefully, this article will answer some questions.

Trumpeters and Tundras (formerly called Whistling Swan) are the only two swan species that are native to North America. Mute Swans are non-native. By 1900, the Trumpeters had been hunted almost to extinction on the continent and had been extirpated entirely from the New England area. Throughout the 1700s and 1800s, Trumpeters were killed for their meat, skins and feathers. Trumpeter skins were, in particular, found to be extremely soft to the touch and were consequently turned into powder puffs. Their long, white feathers adorned a countless number of ladies’ hats. It was the fashion of the times. The quills were highly prized for writing and drawing.

Even John James Audubon, America’s celebrated ornithologist and illustrator, preferred Trumpeter quills for drawing fine detail, such as the feet and claws of small birds. These products were in great demand throughout Europe and North America during the 1700s and 1800s. It is truly ironic that Mr. Audubon, whose life and love of nature inspired the founding of The National Audubon Society, participated in the market slaughter by purchasing Trumpeter quill pens.

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), founded in 1670, traded in Trumpeter Swan and other animal skins and the Native and European trappers hunted the swans throughout their Canadian breeding range. The company held a monopoly on trading of furs and skins there and also in many American wintering areas to where the birds would migrate. By the end of the 19th Century, after most of the swans were gone, the company’s focus shifted towards real estate and the retail sector.

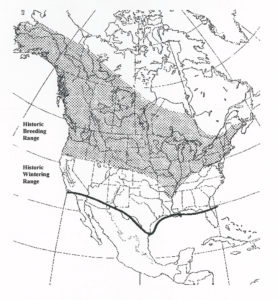

From brief and scattered historical notes and records, Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Manager Winston Banko pieced together the historical distribution of Trumpeter Swans. It appears that the Trumpeter was geographically widespread and abundant across most of North America prior to 1700 (Figure 1). The former wintering range of Trumpeter Swans included southeastern Alaska down the Pacific coast to southern California, across the southern United States through Texas and the Gulf coast to central Florida. Banko also states in his exhaustive report that “At one time or another in the distant past, before man appeared on the North American Continent, Trumpeter Swans must have occurred commonly within nearly every region of what is now the United States.”

A New Englander, Thomas Morton, wrote of the native swans in 1632:

“And first of the Swanne, because she is the biggest of all the fowles of that Country. There are of them in the Merrimack River, and other parts of the Country, greate Store at the seasons of the yeare. The flesh is not much desired of the inhabitants, but the skinnes may be accepted a commodity, fitt for divers uses, both for feathers and quills”.

In 1784, Jeremy Belknap wrote, “It is certain that our swan is heard to make a sound resembling that of a trumpet, both when in the water and on the wing.” In 1878, J.A. Allen stated that the Trumpeter “doubtless was common in Massachusetts 200 years earlier.” Historical estimates of the size of the Trumpeter Swan population are lacking, but early accounts from naturalists and records of swan skin sales from trading companies (17,671 swan skins sold between 1853 and 1877) indicate that this species was numerous. In 1709, John Lawson, the Surveyor General of North Carolina, reported that great flocks of Trumpeters arrived in the winter and inhabited the freshwater rivers.

Gary Ivey is the former Director of The Trumpeter Swan Society (TTSS), based in Plymouth, Minnesota. Mr. Ivey estimates that at least 200,000 Trumpeter Swans existed in North America prior to 1700. An exact number cannot be ascertained, however, because scientific surveys from that time period are lacking. Neither do we know how many Trumpeters existed in New England prior to 1900, when scientists first began tracking birds on a systematic basis. New England may have been a migratory stopover for many of the swans, but certainly some Trumpeters were breeding here during the summer months. Even though the precolonial numbers are brief and scattered, E.H. Forbush, writing in 1925, stated that “The Trumpeter Swan … formerly nested on islands in many lakes or marshes in the latitude of New England and still farther south.”

By 1933, fewer than 70 Trumpeter Swans were known to exist in the wild in the lower 48 states. All of those were found in Yellowstone National Park and the Centennial Valley of Montana. This area offered refuge to the remnant population because natural hot springs kept the water open and available throughout the year in areas so isolated that hunters and trappers couldn’t find them. The Trumpeter population had been reduced to a 60 mile radius encompassing parts of southwestern Montana, eastern Idaho and northwestern Wyoming, including Yellowstone. This discovery led to the establishment of Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in Montana’s Centennial Valley in 1935.

Committed conservationists with TTSS, state wildlife agencies and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, intent on bringing the Trumpeter back from the brink of extinction, have worked diligently to restore their numbers over the past 40 years. The first of many reintroduction programs were begun. Because there were so few birds left, inbreeding was a concern. In 1918, a small flock of 78 surviving Trumpeters had been found in Alberta, Canada. In 1954, a large group of over 2,000 Trumpeter Swans were discovered in Alaska’s Copper River Delta, which led to their removal from the original US endangered species list. More importantly, the eggs of this larger population in Alaska could be used to help the Trumpeters return elsewhere in the Midwest.

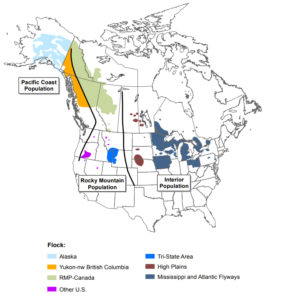

Beginning in the 1980s, Alaskan eggs were carefully collected and transported to begin restoration programs in Montana, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Ontario. Motivated conservationists, scientists and zoos used ingenuity in helping the eggs to incubate. In Wisconsin, wildlife biologists used decoy “swan parents” to teach the small cygnets how to swim and feed themselves. These efforts and others led to the return and growth of North America’s three Trumpeter Swan populations (Figure 2): the Pacific Coast Population (which includes Alaska), the Rocky Mountain Population and the Interior Population (which includes Ontario).

According to the 2015 North American Trumpeter Swan Survey (done every five years) the number of Trumpeter Swans today has rebounded to approximately 63,000 – far from their original numbers – but still a huge accomplishment. The birds that are appearing now in New England and along the Atlantic Flyway are pioneering birds who are exploring and discovering new territories and migration routes and they need all the help they can get from sanctuaries and private landowners. This Trumpeter here in New Hampshire is a direct result of the restoration efforts of many volunteers, biologists and conservationists in the United States. “We are literally watching history happen as it unfolds,” Margaret Smith, current Director of the Trumpeter Swan Society, explained.

The Trumpeter Swan is an “indicator species” of healthy wetlands and waterways. They thrive in clean waters and high-quality habitat that supports countless plant and animal species. “Trumpeter Swans are symbols of hope showing that science, partnerships and perseverance can bring a species back from the brink of extinction,” said Ms. Smith.

In recent years, Trumpeters have been seen in all of the New England states, but these are scattered sightings of usually one to two birds at a time. According to eBird, the highest number reported at one time were four birds in Middlesex, CT in 2007. In Pennsylvania, the first successful nesting pair was reported in 2018. The swan parents were originally banded by biologists at the Clifton Institute in Warrenton, Virginia and were later reported nesting in Pennsylvania. In the mid-1990s Trumpeter Swans began breeding in New York and their numbers have slowly increased. It is not a stretch to imagine a bird flying from upstate New York over to New Hampshire or being blown off course in a storm.

Because our New Hampshire swan does not have a collar, wing tag or leg band, we cannot know for sure where the swan originated, when it hatched, or where it spent the winter. It is possible that it was exploring the area on its spring migration and decided to stop. The New Hampshire swan would have originated from (or be descended from) a restoration program or from a private breeder that helped with one of the restoration programs. Ontario has the closest restoration program to New Hampshire, but they are still actively tagging their swans and this swan has no wing tag. The next nearest program is the Piedmont program in Virginia. Other state restoration programs exist in Ohio, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa. “Descent from these locations would be possible if the swan got lost or managed to fly pretty far east, but again we cannot know for sure” Margaret Smith explained.

“It sounds like [this swan] is just establishing a territory there [in Candia]. My guess is that it is likely to return there next year if it feels safe” said Ms. Smith. “It’s exploring the landscape. If it feels safe there, it will imprint there.” After the age of 2, released swans will “imprint” on an area, which means that it will return to the same area the following spring. It remains to be seen whether it will migrate this fall. Ms. Smith explained that some Trumpeter Swans migrate short distances to a nearby pond or river that remains unfrozen for the winter and others migrate hundreds of miles. Harriman State Park in Idaho, for example, has both wintering and summering swans. The winter flock is just across the parking lot, on the Snake River, a very short distance from the summer nesting site of Silver Lake. (Idaho is at the same latitude on the map as New Hampshire). According to a USDA Forest Service Conservation Assessment from 2002, “the northern populations typically must migrate to the coast or to southern reaches [such as MD, Virginia and NC] in order to find water that is not iced over, while the interior populations and re-established populations tend to be locally migrant or non-migratory, as long as open water is available.”

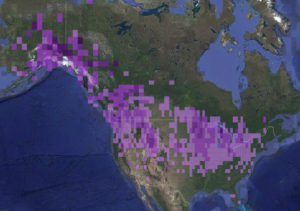

Although the Trumpeter has had a tragic past, it is encouraging to look at the current species map on eBird. If one compares 70 swans in 1933 with an eBird map of 2018 (Figure 3), there is a huge difference in the number of sightings between then and today. In 2018, the Trumpeter Swan was reported (and photographed) from Maine to North Carolina to South Florida. Its breeding and wintering ranges have also vastly expanded since the 20th Century. There is renewed hope for this elegant creature, even though it may not have fully recovered its pre-colonial numbers.

There are no special designations for the Trumpeter in the Granite State, according to Jessica Carloni, a waterfowl biologist at NH Fish and Game. It is not listed as endangered or threatened in New Hampshire, but Trumpeters are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which has been essential to their survival and continued recovery. They were removed from the US Endangered Species List in 1968, the same year the Trumpeter Swan Society was established. That was five years before the Endangered Species Act of 1973. It is currently illegal to hunt Trumpeter Swans, and if one were to be killed, NH Fish and Game would issue a violation and fine.

As stated earlier, the gender of this New Hampshire swan is unknown. Ms. Carloni is guessing that it’s a male because females, she says, have site fidelity and usually return to their natal breeding grounds. She theorized that this bird may have gotten pushed out because of high density in its former flock, wherever that was. Males are slightly larger than females, but at this point in time, we have no other swan to compare it to. The author of this article spotted the swan sitting on a beaver lodge in the marsh, possibly scouting out a future nesting site. (Male birds of different species have been known to scout out future nesting sites, including the Trumpeter, which is also known to prefer Beaver lodges for nesting.) Because they were nearly wiped out, the traditional migration routes for the Trumpeter Swan were disrupted if not completely erased. In general, these swans are in the process of carving out new migratory routes for themselves.

Trumpeter Swans typically settle on ponds, marshes, lakes and rivers. A marsh with 2-4 feet of water is an ideal environment for a Trumpeter. A swan will usually find its mate at its wintering grounds. A Trumpeter can live up to 20 years or more in the wild. When it does mate, which is typically between 3 and 6 years of age, it forms a strong pair bond and mates for life. Beginning in late April or early May, female swans lay 3-10 eggs (one clutch) each year and raise up to that many cygnets, depending upon predation. Cygnets remain with their parents through the first year of life, until they are driven away from their natal grounds by their parents who want to raise another brood. They stay with their siblings or other young swans until about the age of 3, when they begin to seek a mate and look for new marshes on which to nest. As adults, their wingspans can measure up to 6 feet. They need a large expanse of open water in which to take off and land, and their diet consists primarily of aquatic plants and the occasional crustacean.

The original threat to the Trumpeters was market hunting, but Trumpeters still face threats to their survival today. Lead sinkers from fishing lines and lead shot from hunters have settled on the bottom of marshes and ponds where they feed. Thus, many swans have died from lead poisoning. Also fatal collisions with power lines near marshes are not unheard of while the swans are flying low. Lack of state funding for restoration programs is another issue, in part because they are no longer considered endangered.

The disappearance of wetlands to agriculture and development has also slowed restoration efforts. Because clean water and pristine wetlands are essential to their survival, the Trumpeter Swan Society recognizes the importance of saving, and even restoring, wetlands across the United States. Take the State of Iowa, for example. By 1930, the state had drained 90% of its original wetlands to make the land suitable for farming. In 1994, Iowa began its Trumpeter Swan restoration program and used “Trumpeting the Cause for Wetlands” as its slogan. Today, Iowa is a great model for wetlands restoration messaging and education about the importance of wetlands to human health and safety and as home to more than 400 species of plants and animals, Margaret Smith explained.

As for the future of our New Hampshire swan, the vast majority of Trumpeter Swans do migrate to warmer climates by November or December, as the water begins to freeze. Because they feed primarily on aquatic plants while swimming, the species does need open water to survive. Most marshes freeze here in New Hampshire during the winter, so it will be interesting to see if and when the swan migrates this fall, and also if it returns to the Abe Emerson Marsh next spring. Several birders I have spoken to are hopeful that the bird will find a mate this winter and bring it back to Candia. Wouldn’t that be wonderful? Either way, we are happy the swan is here, and we are hopeful for its continued well-being wherever it settles in the future.

Many thanks to Margaret Smith and Gary Ivers of The Trumpeter Swan Society and to David Donsker who contributed valuable information for this article.

Diana Stephens is a freelance writer who lives in New Hampshire. She is the Field Notes Coordinator for New Hampshire Bird Records.

References

Allen, J. 1878. A List of the Birds of Massachusetts, with annotations. Bulletin of the Essex Institute. Vol. 10.

Banko, W. 1960. The Trumpeter Swan: Its history, habits and population in the United States. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. North American Fauna No. 63. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC.

Belknap, J. 1784. A History of New Hampshire. Thomas and Andrews, Boston, MA.

Forbush, E. 1925. Birds of Massachusetts and Other New England States. Massachusetts Department of Agriculture.

Groves, D. 2017. The 2015 North American Trumpeter Swan Survey, A Cooperative North American Survey. US Fish & Wildlife Service, Juneau, AK.

Hudson’s Bay Company website and historical archives. hbc.com accessed June, 2019.

Matteson, S., S. Craven and D. Compton. The Trumpeter Swan, 1995. Publication No. G3647, University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension Service, Madison, WI.

Mealy, N. 1998. Herald Swans’ Reprise, California Wild Magazine, California Academy of Sciences, Vol. 51:2, Spring.

Slater, G. 2006. Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator): A Technical Conservation Assessment, USDA, Rocky Mountain Region Species Conservation Project. http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/trumpeterswan.pdf.

Southwell, D. 2002. Conservation Assessment for Trumpeter Swans. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region. Escanaba, MI.

Trumpeter Swan Society Newsletter, Trumpetings, Plymouth, MN. www.trumpeterswansociety.org.

Read more fascinating stories by subscribing to New Hampshire Bird Records – you’ll also be supporting bird conservation at the same time! Check the website for other free articles and the contents for each issue.