(Photos and story by Pam Hunt)

May brings the rush of migrants back to New Hampshire from their tropical wintering grounds. Among the throngs of birds winging their way north this time of year, few are more popular with birders than the warblers. Among these is the energetic American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla), a boldly-marked species that differs from our other warblers in two significant ways. The first relates to their foraging behavior: although redstarts spend significant time picking insects from leaves like their relatives, they are frequently seen launching themselves off a branch to capture prey in the air like a flycatcher. To facilitate the capture of aerial prey, redstarts have a wider bill and longer rictal bristles (modified feathers that surround the beak) like a small flycatcher. It’s also suspected that the bright patches of orange (in males) or yellow (in females) on redstart tails serve to startle insects as the birds actively fan their tails while they move through the foliage.

And it is in the development of plumage that redstarts are also outliers within the warbler clan. Male redstarts take two years to obtain their bold black and orange plumage, with one-year-old birds looking much like females. If you see what looks like a female singing, look extra closely and you might see a few black feathers around the face or breast that indicate it is actually a young male. Why male redstarts exhibit such “delayed plumage maturation” is unclear, but it might have something to do with minimizing direct competition with more mature birds. Indeed, studies of redstarts in New Hampshire suggest that yearling males are less likely to attract a mate than older ones and are often relegated to less suitable habitats such as older forests or those with more coniferous trees.

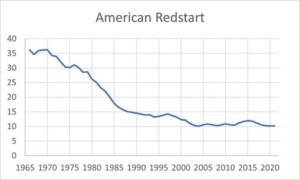

This phenomenon of “extra” males would imply that females are less common, and studies of redstarts on their Caribbean wintering grounds provide a possible explanation. Outside the breeding season, males and females defend exclusive territories, and males are socially dominant. Females are thus forced into poorer (often drier) habitats and are less likely to survive if conditions deteriorate. This discrepancy between male and female survival has likely been exacerbated by human alteration of habitats on the winter grounds. If there was more good habitat, females would not be as likely to be excluded from it by males. Declines in redstart populations (Figure 1) are likely the result of factors operating in winter as described here, and in summer through maturation of young forest habitats and possibly changes in predator populations.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Hardwood/Mixed Forest

- Migration: Long-distance

- Population trend: Declining

- Threats: Predation, Collisions, Habitat Loss

- Conservation actions: Manage forests for mid-successional stages, maintain a bird-friendly yard.

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available here. Full species profiles in the format of “Bird of the Month” are now available here.

Cover photo: Adult male American Redstart.