(Story and photos by Pam Hunt)

The Isles of Shoals off the New Hampshire coast are the southernmost breeding site in the world for the Black Guillemot (Cepphus grylle), a small alcid – the group of birds that includes puffins – found on both sides of the north Atlantic and across much of the Arctic. Although some colonies in the far north may contain thousands of pairs, guillemots are less gregarious than most other alcids, and tend to occur in colonies of fewer than 50 pairs. Here at the southern edge of their range, there may be only 10-15 nests each year at the Isles of Shoals.

These nests are typically located in rocky crevices, under detritus such as driftwood and abandoned fishing gear, or in burrows. The birds sometimes line these with pebbles, pieces of vegetation, or broken shells, and here lay two eggs starting around late May. The eggs are incubated for about a month, and upon hatching the chicks are fed for roughly 40 days before they are ready to head to sea. Still unable to fly, they scramble down to the ocean at night and shortly thereafter leave the immediate vicinity of the colony. At this point they are completely independent of their parents and feed on their own, but aren’t capable of sustained flight for 3-4 more weeks.

Unlike most alcids, guillemots feed in relatively shallow waters, where they use their wings to swim underwater in search of fish and invertebrates on the ocean floor. Because of their preferred foraging habitat, they are the most likely alcid to be seen from shore in New Hampshire during the winter, when some even enter harbors or coastal coves. Many also remain near their breeding colonies as long as the water remains ice free.

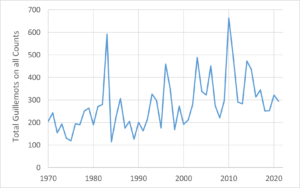

Because they nest out of sight and often at low densities, data on Black Guillemot populations are limited. The population in the Gulf of Maine and eastern Canada is estimated between 150,000 and 200,000, and available data suggest it is increasing. There is hint of this increase in Christmas Bird Count data for Maine and New Hampshire, as shown in Figure 1. Some of this increase could be the result of increased effort however, and counting conditions probably account for much of the observed variation. It can be hard to find and count little gray and white birds on the ocean in the best of times, and much harder if there are significant waves!

Those little gray and white blobs floating offshore are the version of the Black Guillemot usually seen by shore-based observers. They molt out of their solid black plumage in September, keeping only their large white wing patches, and retain this appearance until late winter. By this time they’re also starting to return to their nesting colonies. Juveniles look similar to the winter adults except for dark barring in the wing patch. So if you’re birding the New Hampshire coast this fall or winter, don’t be looking for “black” guillemots.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Coastal

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Increasing

- Threats: Pollutants (oils spills, heavy metals), climate change, fishing nets

- Conservation actions: More data are needed on population trends and magnitudes of threats