(by Pam Hunt)

The following is an increasingly common sight at bird feeders throughout the Granite State. You’re watching your feeders when suddenly the songbirds scatter as a brown blur streaks through the yard, perhaps ending its flight by perching in a nearby tree – with or without one of your juncos. We may bemoan this hawk taking the life of the smaller bird, but that’s what “accipiter” hawks like Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperi) – which is almost certainly the bird involved – do, and it’s not really our role to judge them for it. Besides, we should instead recognize the Cooper’s Hawk for its unsung conservation success story.

Over a century ago, birds of prey were near-universally reviled because of their perceived role in killing domestic poultry and game species, and from this the Cooper’s Hawk earned the nickname “chicken hawk.” They were shot indiscriminately across a large portion of the east and didn’t receive widespread legal protection until the 1960s. At the same time, they were being negatively affected by persistent organic pesticides like DDT, which reduced reproductive success just like it did in high profile species like Bald Eagle and Peregrine Falcon. As a result, Cooper’s Hawk was listed as threatened or endangered in many states, including New Hampshire. After DDT was banned, populations rebounded much more quickly than those of other affected raptors, and the chicken hawk managed to get of the threatened list with no other help from us.

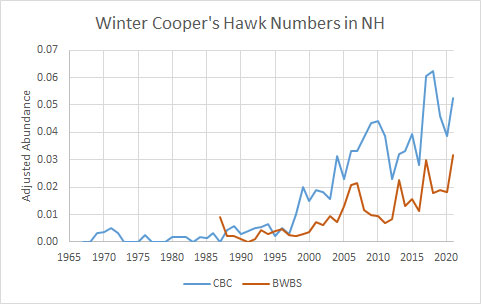

As it recovered, it also began to change its behavior, and adapted to urban and suburban landscapes. All it needs is a somewhat secluded tree in which to nest (perhaps in a city park) and a reliable source of food, the latter provided by abundant pigeons, starlings, House Sparrows, and yes, feeder birds. Now it’s generally believed that Cooper’s Hawks are the most abundant backyard raptor in the United States. Data from New Hampshire bear this out. The graph below shows numbers reported on both the Christmas Bird Count and NH Audubon’s Backyard Winter Bird Survey, and as we’ve noticed in other “Bird of the Month” graphs these two data sets are a remarkable match for each other.

Given this recovery, many might ask whether Cooper’s Hawks pose a threat to other bird populations. After all, their diet is almost entirely small-to-medium sized birds, many species of which are steeply declining. While it’s certainly possible that there are some such effects, it’s critical to realize that birds of prey are a natural part of our local ecosystems, and that there are far greater threats to songbirds in the form of habitat loss, cats, and windows. The latter may even be a significant source of mortality to the hawks as well, with a study in Arizona estimating that almost three quarters of known deaths in an urban population were from collisions with buildings. They may be adapting to the human environment, but this doesn’t mean they pay attention to obstacles while chasing prey at bird feeders.

No discussion of the Cooper’s Hawk would be complete without mentioning the challenges in identification. The “accipiter” hawks are notorious in this regard, especially in their immature plumages. Size can be helpful, but because males are much smaller than females our three species overlap significantly. Sharp-shinned Hawk is the smallest, and the males are quite tiny indeed – weighing less than a Mourning Dove. At the other extreme (leaving the massive goshawk out for this article) a female Cooper’s is the size of a crow. There’s actually no overlap in weight between the two species, but none of us can actually access it this in the field, and in linear measurements the female Sharp-shinned is only marginally smaller than the male Cooper’s. There’s not space here for an exhaustive treatment (check your field guide!), but a good starting point is the shape of the tail. In Sharp-shinned Hawks all the tail feathers are roughly the same length, giving the tail a squared-off look (or slightly notched when perched). In contrast, the tail feathers of a Cooper’s get shorter away from the center and give a rounded appearance. You can see the difference in the lengths of the tail feathers by comparing the Cooper’s and Sharp-shinned photos that accompany this article.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Hardwood/Mixed Forests and Developed

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Strongly increasing

- Threats: Chemical contaminants, collisions (especially in urban areas)

- Conservation actions: Reduce pollution

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available at: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/the-state-of-the-birds/