(Story and photos by Pam Hunt)

Few birds convey the spirit of winter and the holiday season like the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). This seems an appropriate symbolism, what with the males’ bright red plumage livening up our otherwise snowy New Hampshire landscape. But as many long-term residents of the state can tell you – this was not always the case.

Prior to the early 1900s, cardinals were not a regular member of the New England avifauna, and were largely unknown north of New Jersey and the New York City area. By the 1930s and 1940s they started to increase to our south and began to appear in New Hampshire, with the state’s first records in 1931, 1944, and 1949. The real increase began in the late 1950s, highlighted by a regional “invasion” up the Connecticut river Valley in 1957. In that year birds were recorded as far north as Haverhill, with a possible sighting all the way up in Pittsburg. The first evidence of nesting came from Hanover shortly afterward, in 1960.

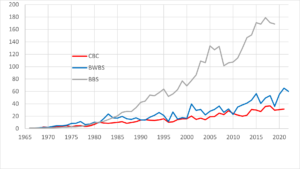

Increasing cardinal populations (as well as those of Tufted Titmice and Northern Mockingbirds) led Massachusetts to begin a dedicated survey in the early 1960s, and New Hampshire Audubon followed suit in 1967 with what later became the “Backyard Winter Bird Survey.” The nationwide Breeding Bird Survey came into being in 1966 and during this same time the Christmas Bird Counts were increasing in popularity. As a result we have three independent data sets on bird populations that we can look at with respect to changes in cardinal numbers starting in the mid-1960s (Figure 1).

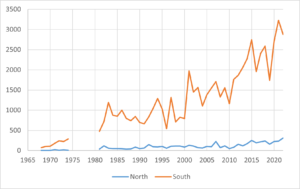

No matter how you slice it, cardinals have increased dramatically since all these surveys began, and are now many many times more abundant than they were 50 years ago. They are still far more common south of the White Mountains (Figure 2) and rarest of all in far northern New Hampshire. Cardinals didn’t start becoming regular on the Errol and Pittsburg CBCs until the 1990s, and total numbers on these counts are often lower than at a single southern feeder during the BWBS!

There is much speculation on the cause of the Northern Cardinal’s northward expansion over nearly a century (it’s also expanded west, although a little more slowly). Warming climate could certainly play a role, including the decreasing snow cover facilitating ground foraging. But other factors are certainly involved, especially since many areas colonized in the late 1900s still saw regular snow cover. In the Midwest, the expansion is somewhat tied to habitat change, as both forests and prairies (neither ideal cardinal habitat) were converted to parks and residential areas. In this case the cardinal is similar to other NH shrubland birds that expanded with initial forest clearing, but its less specialized habitat needs have allowed it to thrive while towhees and thrashers continue to decline.

Finally there’s the question of bird feeders. There is no doubt that early records were often at feeders, and cardinals remain most frequent in human-dominated landscapes, and it’s thus likely that supplemental food aided invaders at the very northern edge of the range. Whether feeders remain as important today is less clear, since available data indicate that birds are generally not dependent on feeders. In the end, no matter which factors were behind the increase, cardinals remain exceptionally successful here in the Granite State – possibly adapting to our climate and landscape after initial colonization – and will continue to brighten up our winter yards for years to come.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Developed, Shrublands

- Migration: Non-migratory

- Population trend: Strongly increasing

- Threats: cats, collisions

- Conservation actions: Make yards and buildings safe for birds