(by Pam Hunt)

For most shorebirds, fall begins in July while many of our local songbirds are still nesting, and peaks in August and early September when over 15 species have been recorded along the New Hampshire coast. All these birds are stopping at local beaches and mudflats for one reason: replenishing their fat reserves for their long migrations between arctic breeding areas and wintering sites in the Caribbean and South America. Most of the thousands of birds we see in New Hampshire during their stopovers are two species: Semipalmated Plover and Semipalmated Sandpiper, but one of the most sought-after is the much larger and distinctive Whimbrel.

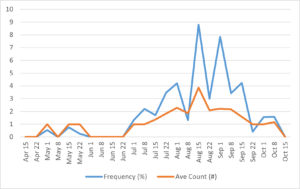

The Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) is the largest regularly-occurring shorebird in the state, and is easily identified by its long decurved bill. It uses this bill to reach into burrows of intertidal invertebrates, but also picks prey directly from the surface the sand or mud. Whimbrels sometimes occur inland, where they feed on insects and even berries in short grassy areas and heathlands (e.g., blueberry barrens in Maine). In New Hampshire they are far more likely in fall (Figure 1), but even then are relatively rare. We don’t have good trend data for the species at the state scale, although anecdotally it appears to be less common than before 2000.

The perceived decline of Whimbrels as a migrant in New Hampshire may be symptomatic of an overall decline across the species’ continental range. Counts during fall migration in Virginia and along the northern coast of South America dropped significantly between 1980 and 2010, and as a result the species is now a focal species for hemispheric shorebird conservation planning. Shorebirds in general are showing some of the strongest declines of any group in North America, at least in part because of their long migrations and the diversity of threats they encounter along the way.

Migrant shorebirds are heavily reliant on relatively few stopover sites along the Atlantic coast. These are areas where the majority of birds stop to rest and feed before continuing their journeys, and their next steps might even be non-stop overwater flights of hundreds of miles. Because of this, they are vulnerable to any threats that effect their survival or resources at stopover, including habitat loss, hunting, and changes to food supply. Coastal development continues to chip away at formerly intact marsh and beach systems, but of perhaps of more concern at present are the gradual effects of climate change. As sea levels rise, foraging habitat becomes increasingly flooded and perhaps inaccessible even to long-billed species like the Whimbrel. Changes in the arctic may be even more damaging but remain little studied and increasing storm frequency during fall migration is likely to affect both birds and their habitat (see box on page 38 of “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds”).

Where suitable stopover habitat exists, shorebirds are frequently in conflict with humans who want to use it for recreation, resulting in more frequent disturbance of birds when they need to be focusing on resting or foraging. Several studies have found that shorebirds subject to more regular disturbance build up lower fat reserves, and are thus less likely to survive the next leg of their migration. And even if they do, another threat is in store far to the south. Although fully protected in North America, shorebirds are still extensively hunted for sport and sustenance in the western Caribbean and northern South America, and some analyses indicate that most annual mortality occurs during fall in this region. Progress is being made to introduce more stringent hunting restrictions – and some outright bans – in these areas but changing long-established traditions will take time.

So if you’re lucky enough to find a Whimbrel this fall along the coast, wish it well. It has a long journey ahead of it, and may encounter a gauntlet of storms, lost habitat, and shotguns as it navigates over a thousand miles to its winter home.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Coastal, Grasslands

- Migration: Long-distance

- Population trend: Declining

- Threats: Habitat loss, hunting, climate change, disturbance

- Conservation actions: Protect coastal habitats, minimize disturbance to shorebirds (e.g., keep dogs on leashes)

See also our shorebird page on the NH Audubon website: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/coastal-shorebirds/

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds” is available at: https://www.nhaudubon.org/conservation/the-state-of-the-birds/