(Pam Hunt)

We are excited to present a new feature to NH Audubon’s eNews: “Bird of the Month.” Written by Dr. Pamela Hunt, Senior Biologist for Avian Conservation, each installment will focus on a single species of New Hampshire bird with a story to tell. These may be increasing or declining species, those with a special connection to the Granite State, familiar yard birds, or any of the above. Each profile will reference information in our “State of the Birds” report, including conservation actions that people can take to help the focal species or its habitat. Thus, with no further ado, allow us to introduce this month’s star: the Winter Wren, a species which also happens to grace the cover of “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds.”

Winter Wrens are short-distance migrants that winter primarily in the southeastern United States in thickets and riparian areas, and it is probably from this that they got their common name. Perhaps because of a warming climate, the species is increasing as a winter bird in southern New England as far north as parts of New Hampshire. The best way to find a Winter Wren in winter is to find an area of dense vegetation near running water and listen for their sharp chip notes. But not all winters are

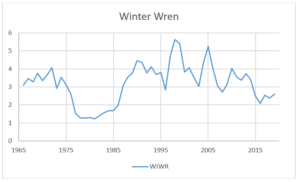

equal, and particularly cold ones can be hard for this species, even well to the south. In the New Hampshire population graph below, you can see a dramatic decline in the 1970s. This is believed to be related to several unusually cold winters in the southern United States that resulted in high mortality – a population-level blow that Winter Wrens took roughly a decade to recover from. The ups and downs in the 1990s and 2000s are likely related to the same phenomenon, making it hard to ascribe a trend to this half century of data. Whether Winter Wrens are increasing or decreasing depends on which subset of years are examined, and the best we can really say is that their populations are probably “stable with fluctuations.”

Even though Winter Wrens are not a species of conservation concern, there are still things you can do to help them out. Like all migrants, they are vulnerable to predation by cats and collisions with buildings, and mitigating these threats is beneficial to all birds. They almost never come to bird feeders, but if you leave brushpiles in the woods near springs and streams, you might still attract one to your yard now and then!

State of the Birds at a Glance:

Habitat: Spruce/Fir and Hardwood/Mixed forests

Migration: Short-distance

Population trend: uncertain (probably stable, but see above)

Threats: unknown, but possibly forest loss or climate change

Conservation actions: Keep cats indoors, retain or create brushpiles and other cover in suitable habitat

More information on “The State of New Hampshire’s Birds”

Photo by Susan Wrisley; recording retrieved from https://www.xeno-canto.org/, recorded by David Eberly in Addison County, VT in July 2015.