(Story and photos by Pam Hunt)

March marks the beginning of waterfowl migration, and despite recent cold snaps there is a lot of open water in New Hampshire for ducks and geese to use. Among the birds moving north this month will be one that never left some parts of the state: the Common Merganser (Mergus merganser). During winter and migration these large diving ducks congregate in open water of lakes, large rivers, and estuaries, but are rarely seen on the ocean. The latter is the realm of the Red-breasted Merganser, and knowing the two species proclivities for fresh (Common) or salt water (Red-breasted) is a good first clue in identification. Because of their size and relatively long bills, Common Mergansers are also sometimes mistaken for loons. They are significantly smaller however, and lack the extensive white checkering of adult Common Loons. Females may be confused with immature loons, but have a thinner and red bill and a rusty head with a shaggy crest.

But like loons, mergansers are fish eaters, and their bills are uniquely adapted to this diet. The bill is long and thin, in stark contrast to the typically flat bill of many ducks, and the edges are serrated to facilitate a firm grip on their prey. This adaptation has given mergansers one of their colloquial names: sawbills. If you watch mergansers foraging, you’ll see them dipping their heads into the water as they swim, and when fish are sighted the bird will make a slight leap forward before plunging into the water in pursuit. At this point the duck propels itself with its feet and typically stays under water for 20-30 seconds. If there are large schools of fish in an area, you might see several mergansers hunting in a flock and diving somewhat synchronously.

Common Mergansers are cavity nesters, and use large hollow trees and nest boxes along more secluded sections of lake and river shores. They will sometimes investigate other tall hollow structures as potential nest sites, and there is no shortage of stories about people finding one in their living room after going down a chimney and coming out the wrong end. Assuming they find a more suitable nest site than a chimney, a female Common Merganser will lay up to a dozen eggs and incubate them for about a month. When the chicks hatch, the whole family will head to the water, and it’s common to see a female merganser trailing numerous fluffy ducklings while boating on New Hampshire’s lakes and rivers. Common Mergansers are sometimes seen with 20 or more ducklings, and this is generally the result of broods mixing up after they’ve left the nest.

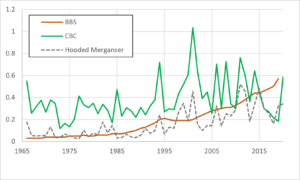

Like most waterfowl, Common Mergansers are increasing in New Hampshire and the Northeast, as shown in Figure 1. The ups and downs in the Christmas Bird Count data are probably based on the extent of open water, but the highs have been much higher in recent years than they were in the 1970s and 1980s. This could also be attributed to warmer winters and thus less ice, so the Breeding Bird Survey trend is probably a more appropriate metric for assessing population trend. Figure 1 also includes the winter trend for our other breeding merganser – the Hooded – which is also showing significant increases.

Increasing merganser populations are believed to be a result of improved water quality, especially declines in chemicals like DDT. As fish-eating birds, mergansers were impacted in the same manner as eagles, pelicans, and other “poster species” of the DDT era, and conservation efforts targeting those more charismatic birds have benefitted other species in the same ecosystems. At the same time, other contaminants still threaten mergansers, including mercury, lead, and organic chemicals like PCBs. Mergansers also suffered from reduced prey ability at the height of the acid rain era, when lakes became increasingly inhospitable for many species of fish.

Thankfully, the days of DDT are over and acid rain is less of a problem for aquatic habitats than it used to be, and Common Mergansers have recovered nicely over most of their range.

State of the Birds at a Glance:

- Habitat: Lakes and Rivers

- Migration: Short-distance

- Population trend: Increasing

- Threats: Heavy metals, contaminants, oil spills, shoreline development

- Conservation actions: Shoreline protection

NH Audubon’s “Backyard Winter Bird Survey” will occur on February 11-12, 2023. Find details here, plus how to participate.